Advanced Entrepreneurship Theory: Opportunity, Symmetric Information, Schumpeter, and Kirzner

ABSTRACT

Cross-incompatibility is a philosophy of science neologism that refers to a cause of the conceptual phenomenon of disagreement (i.e., agonism) that results between philosophical approaches (in the same field) striving to treat (or explain) the same target phenomenon (with the same representational ideals) via different idealization strategies, inclusion criteria, and fidelity criteria. This paper observes, evidences, and then coins cross-incompatibility as an important driver in the entrepreneurial opportunity debate between the Austrian and Neoclassical camps of economic theory. Stylized as a literature review of the philosophical discussion surrounding the idealized entrepreneur’s role in competitive markets, this paper offers fresh philosophical perspectives on (unfortunately) seldom-treated (yet worthy) literature with stimulating examples and implications to startup founders, policymakers, executive mangers, business students, and venture capital strategists.

For more information on the foundational concepts underlying this paper, please see Michael Weisberg’s Simulation and Similarity and the economic philosophy work of Joseph A. Schumpeter and Israel M. Kirzner (or visit my personal website, murataj.com/discourse, for condensed notes).

Keywords: Austrian economics, neoclassical economics, Schumpeterian entrepreneurship, Kirznerian entrepreneurship, representational ideals, idealization, fidelity criteria, inclusion criteria, philosophy of science, agonism, market opportunity, market equilibrium, economic development, asymmetric information, disruption, rent-seeking, cross-incompatibility.

INTRODUCTION

The debate about the ontology of entrepreneurial opportunity (viz., whether opportunity is constructed by the entrepreneur or discovered by the entrepreneur) has its roots in the Neoclassical-Austrian economics schism and is important to both entrepreneurial praxis and market regulation policy. The constructivist camp (of Schumpeter) holds that entrepreneurs are creative, equilibrium-disrupting agents who create opportunities and develop new market baselines by “creative destruction;” (in vernacular, disruption); the discoverist camp (of Kirzner) holds that entrepreneurs are “alert,” rent-seeking arbitrageurs who take advantage of market information asymmetries to exploit opportunities and thus equilibrate markets.

I claim that Schumpeter and Kirzner—the respective “founders” of each camp—extend different economic models that strive for P-generality in explaining entrepreneurial opportunity. I then argue that Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s models breed debate by striving for P-general explanations of the same possibility class with two distinct sets of inclusion and fidelity criteria. I coin the term “cross-incompatibility” to describe this type of debate trigger.

1. THE ROOTS AND IMPORTANCE OF THE OPPORTUNITY DEBATE

Understanding the origins of the opportunity debate is necessary to discussing its importance, understanding its camps, and (later) comprehending the models at the heart of the disagreement between those camps. The opportunity debate originates from debates between Neoclassical vs. Austrian economics on market equilibrium, market information symmetries, and the market role of entrepreneurs. The constructivist camp aligns with the Neoclassicals, and the discoverist camp aligns with the Austrians. Understanding these economic theories at a non-trivial level is necessary to comprehend the idealizations central to the models employed by the camps in this debate, and later to establishing the concept of cross-incompatibility.

Neoclassicals conceive of the entrepreneur as a disruptor, and benefit from created opportunities because these are germane to their assumptions of symmetric information and static equilibria. The Austrians conceive of the entrepreneur as an equilibrator and benefit from discovered opportunities because these confirm their assumptions of asymmetric information and dynamic equilibria. Created opportunities make entrepreneurial innovation the practical imperative and imply that markets have social problem-solving capacity; discovered opportunities make entrepreneurial “alertness” the practical imperative and imply less wieldy markets. Below, I examine each of these premises in depth.

1.1 Neoclassical vs. Austrian Market Equilibrium and Created vs. Discovered Opportunity

If entrepreneurs create the opportunities they exploit, they effectively create new market equilibria (Schumpeter 1932, 62-70). If entrepreneurs discover the opportunities they exploit, they only alter extant equilibria (Kirzner 1978, 1-22). While these viewpoints are not mutually exclusive in practice, they are in theory—the endogeneity vs. exogeneity of market opportunities support the concepts of static (Neoclassical) vs. dynamic (Austrian) equilibria, respectively. Below, I explain why each discipline prefers either viewpoint by considering them in context.

Neoclassical theory conceives of the Schumpeterian (read: constructivist) entrepreneur. The Schumpeterian entrepreneur poses no threat to Neoclassical static equilibrium because they take markets from one (less efficient) “level” of equilibrium to a new (more efficient) “level” of equilibrium by innovation. The Schumpeterian entrepreneur is thus a “creative destroyer,” and his activity does not “exert forces” on equilibrium—rather, the entrepreneur’s dynamism is “economic development,” i.e., dynamism between different “levels” of equilibria rather than within equilibria (c.f., the Austrian view of dynamism within equilibria).

Thus, the Schumpeterian entrepreneur’s innovation “ratchets” the economy to another “level,” changing the point about which the “pendulum” of equilibrium swings and resulting in a “deeper, broader stream of goods” (Schumpeter 1934, 62-74). Schumpeter’s view thus allows for economic dynamism without violating static equilibrium; it is germane to neoclassical theory while accommodating for a characteristic observed in real economies. And because innovation comes from within the entrepreneur—i.e., the opportunity is endogenous (created)—there is no threat to the central Neoclassical concepts of perfect competition (i.e., e.g., it is not that perfect competition failed to price the opportunity, but rather that the opportunity was never-before-conceived).

On the other hand, if entrepreneurs exploit extant opportunities, then Neoclassical perfect competition has failed because market rents must therefore exist prior to innovation (i.e., new but symmetric information) as rent-seeking opportunities for entrepreneurs to exploit. In this case, entrepreneurs make entrepreneurial profits by effectively correcting old markets (i.e., exploiting rent-seeking opportunities by seeking the rents). This opportunity ontology implies that market dynamism occurs both within and between market equilibria. This ontology stands in direct contrast with neoclassical principles of static equilibrium but aligns with the Austrian school’s principles of competitive price discovery (a la Hayek).

The Austrian Kirznerian (read: discoverists) entrepreneur is the Schumpeterian entrepreneur’s doppelganger in a situation of dynamic equilibrium. The Kirznerian entrepreneur is a market-equilibrator who is specially “alert” to opportunities for entrepreneurial profit. When this entrepreneur identifies underpriced resources to apply to some more efficient, more valuable use, he corrects the discrepancy and earns rents. This process of correction implies that the equilibrium price (and quantity) before and after the entrepreneur’s exploitation changes—without necessitating “creative destruction”—because of unexploited, exogenous market artefacts that may continuously exist as vacuums of market competition until exploited. Thus, exogenous (read: discovered) opportunities seem to imply that Neoclassical perfect competition does not exist, because equilibrium cannot be static.

So, rather than disrupt equilibria via “creative destruction,” the Kirznerian entrepreneur constantly nudges the market toward equilibrium through competitive price discovery. The Kirznerian entrepreneur arbiters underpriced resources from markets with less efficient resource use-cases to markets with more efficient, more valuable use-cases.

Information is central to equilibrium, because information asymmetries prevent perfect competition and allow Kirznerian entrepreneurs to discover market opportunities. In the process of discovering opportunities to exploit, the Kirznerian entrepreneur equilibrates the market and satisfies Austrian views of dynamic equilibrium. However, the Kirznerian entrepreneur contradicts Neoclassical principles of static equilibrium and symmetric information. Herein lies the crux of the equilibrium debate.

With this overview of the equilibrium debate concluded, I move on to this crux: whether market information is symmetric or asymmetric.

1.2 Knowledge of Opportunity under Neoclassical vs. Austrian Information Symmetries

Information symmetry indirectly reflects whether opportunities are created or discovered. Information symmetry refers to a property of markets whereby information about the fair value of all goods (and their uses and manufacturing processes) is equally knowable by all market participants (i.e., attainable for a price). Information symmetry is necessary to neoclassical perfect competition and static equilibrium theories; rents can be eliminated only if every market participant has full knowledge of all relevant pricing, quantity, process, and usage information to make value decisions. In turn, information symmetry is necessary to static equilibrium because prices can reflect economic value perfectly via tatonnement only if the true value is knowable (and despite rational ignorance).

Consider: If all market information that exists is symmetric, then perfect competition holds, and the market has destroyed all opportunities to take advantage of that information and earn rents. Therefore, entrepreneurial opportunity must come from information that does not yet exist. Since Schumpeterian entrepreneur creates new solutions, he introduces new (not previously extant) information into the market. This is germane to neoclassical assumptions about symmetric information because, if the entrepreneur is an innovator (and the opportunity is therefore created), then it is no problem that the rest of the market could not figure out the same opportunity, since information about the opportunity reflected in the innovation did not previously exist. Once the entrepreneur enters the market, the market knows of the innovation, and its rentability is erased—but the economy has “developed” (Schumpeter 1932, 63-75).

Thus, for Neoclassicals, market opportunities must be created by “genius” entrepreneurs. Only if opportunities are created is perfect competition not threatened, because the entrepreneur is simply the first in a market that they themselves create; they are not party to special, asymmetrically distributed competitive information—a point of debate with the Austrians.

Information asymmetry, on the other hand, means that not all information is equally knowable in the market (even for a price). Asymmetry arises because knowledge “funnels” through markets since participants specialize, focusing only on what is pertinent to their role and experience (Hayek 1945). This asymmetric information implies that opportunities for rents can exist exogenously due to ignorance and oversight, which implies that market participants do not seek additional information not because the diminishing marginal returns of information acquisition, but rather because they are sheerly ignorant of the existence of information. This information may point to more valuable “alternative uses” for an underpriced resource (Hayek 1945; Kirzner 1978; Casson 1982).

So, asymmetric information is anathema to Neoclassical perfect competition. If market participants can be sheerly ignorant of information regarding the true value of a conduit, tatonnement may privilege participants that are more “alert” to specific uses of a resource over others. Equilibrium cannot be static, but must be dynamic, because the price of a resource may change as new use-cases—new opportunities—for resources are discovered by especially “alert” market participants. Consequently, if “alert” participants across different “alertness” classes are privy to distinct opportunities left unarbitraged due to sheer ignorance, perfect competition cannot exist; no amount of information acquisition expense can guarantee that a participant will be able to identify and make use of information outside of their “funnel.”

Hence, for the Austrians, market opportunities are necessarily discovered by “alert” market participants: the Kirznerian entrepreneurs. This “alertness” differentiates entrepreneurs from other market participants and enables them to earn rents (i.e., entrepreneurial profits) in dynamic markets. Entrepreneurs exploit opportunities relayed to them by asymmetric information to coordinate dynamically underpriced resources towards fulfilling more rentable alternatives. In the process, entrepreneurs equilibrate the market by altering equilibrium quantity and price to reflect known alternative use-cases of resources, spreading this knowledge to imitators (Casson 1982).

In sum, Neoclassical economics necessitates that opportunities be created by innovative entrepreneurs because only then can perfect competition, static equilibrium, and information symmetry hold. In contrast, Austrian economics holds that opportunities are discovered by especially “alert” entrepreneurs as part of the competitive price discovery process that results in dynamic equilibria, all due to asymmetric information. But the importance of the opportunity debate is not solely theoretical; below, I cover the practical implications of the ontology of opportunity.

1.3 Entrepreneurial Praxis and Policy Importance of Created vs. Discovered Opportunity

Whether opportunities are created or discovered is central to the practice of entrepreneurship, and the deeper understanding of how Neoclassical vs. Austrian theories interact with opportunity (developed above) helps make sense of why this is the case. Consider the United States economy under those two different views. Schumpeter sees a circular auction where imitating an innovator is not rentable; Kirzner sees a dynamic crowd where innovators are just as likely—if not privileged—to take rents.

Schumpeter’s ontology implies that entrepreneurs should prioritize product development (since developing an innovation is the best way to create opportunity). Kirzner implies that entrepreneurs should prioritize product-market fit (and thus focus more on discovering arbitrable unmet needs). The Schumpeterian entrepreneur enters the market only when their innovation is perfected, and they iterate prototypes incessantly and privately. The result is a revolutionary masterpiece, the rentability of which is destroyed by imitators. In contrast, The Kirznerian entrepreneur prioritizes primary market research and copies aspects of what he sees, his imitation the reason for his rents. The result is a chimera, the rentability of which is ensured by ignorance.

The ontology of market opportunities also has non-trivial implications for market regulation policies. Markets have the potential to enable social justice and upward mobility under created opportunities independent of government regulations. Under discovered opportunities, unregulated markets may impede socioeconomic mobility due to information asymmetries interacting with systemic inequality. The Schumpeterian entrepreneur could spontaneously produce innovations to problems such as climate change without government subsidies; the Kirznerian entrepreneur would need to be incentivized with government subsidies. Patently, the opportunity debate is important, both theoretically and practically.

The focus so far was on conceptualizing the Neoclassical market environment (where the Schumpeterian entrepreneur innovates), vs. the Austrian market environment (where the Kirznerian entrepreneur arbitrates). The constructivist and discoverist models (described below) strive for P-generality and describe the same reality; yet they reside separately in these idealized Neoclassical and Austrian economies. Hence, understanding the theoretical landscape underlying those models was not in vain. The Neoclassical and Austrian theories provide the idealizations that Schumpeter and Kirzner use in their models, and the lenses by which they understand the opportunity issue.

2. DISCOVERIST AND CONSTRUCTIVIST MODELS OF MARKET OPPORTUNITY

The constructivist camp, fathered by Schumpeter, holds that opportunities arise from entrepreneurial action; whereas the discoverist camp, fathered by Kirzner, holds that opportunities exist in the market independently of entrepreneurs. Both camps rely on Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s models of entrepreneurial-market interaction; these models embody the disagreements at the core of the opportunity debate. For this analysis, only Schumpeter’s and Kirzner’s writings are considered, representative of their respective camps.

In his discourse, Schumpeter describes a conceptual model idealized to work within the static Neoclassical economic paradigm: his model strives for P-generality; its inclusion criteria prioritize entrepreneurial “genius” over “external forces;” and its fidelity criteria are restrictive and prioritize “fit” of target explanation with Neoclassical theories. Kirzner’s conceptual model is idealized to work within the dynamic Austrian paradigm: his model also strives for P-generality, but its inclusion criteria prioritize information asymmetries and competitive price discovery; its fidelity criteria are stringent and concerned with best representing real markets, although Kirzner inevitably satisfices Austrian assumptions. Below, I will elaborate on these conceptual models by extracting them from their discursive representations, to later enable an explanation of the underlying disagreement about P-generality, inclusion, and fidelity criteria.

2.1 Schumpeter’s Periodic Creation Model and Neoclassical Approach to P-generality

Schumpeter—representative of the constructivists—holds that, due to the static nature of perfect competition and symmetric information, opportunities must be endogenous to entrepreneurs (i.e., exogenous to the economic system) because the market ruthlessly prices away rents (Schumpeter 1934, 65). Schumpeter’s model of opportunity is periodic in the sense that, despite static equilibrium, opportunities instantiate as “waves of the economy” that “do not return to the same level” but rather raise the “level of circular flow” (62-77). The cause for these opportunities, which instantiate as “new combinations” of labor and capital that force the “agents of the static economy…to serve new functions” is the entrepreneur, a creative genius whose innovations “occur whenever the entrepreneur needs them;” “the economy does not grow into higher forms by itself” (64-5; 71; 75). Thus, opportunities are temporary periods of disequilibrium, and the rise in the baseline for circular flow is “upward movement…which results from entrepreneurial profit and interest” (80).

So, Schumpeter understands the opportunity issue as fundamentally about economic development (Schumpeter 1934, 62-70). Economic development means the movement of the circular flow of static equilibria towards higher “levels,” such that “oscillations” around the equilibrium escalate “up” a hierarchy of needs (where higher-level needs arise as lower-level needs are satisfied); and the overall need-satisfaction capability of the economy is improved because development permits “a higher level of production of goods in the wider economy” (63-67; 71-72). This way, Schumpeter accommodates the Neoclassical idealization that “an economic equilibrium, once attained, will be maintained” while reflecting that real economies do “not only behave in a static way, but…actively…in…development” (Schumpeter 1934, 70-86).

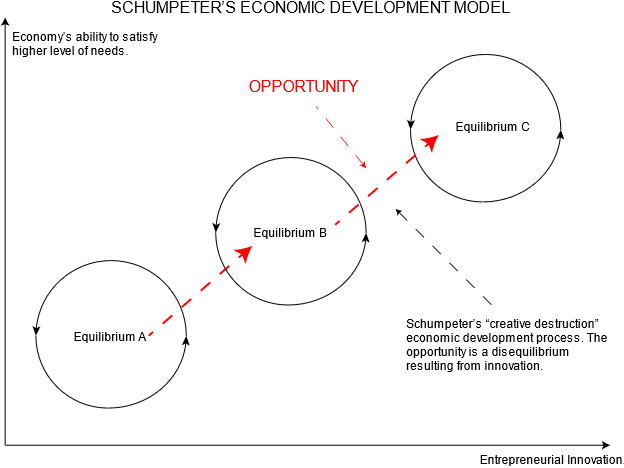

From this paraphrase, an image of Schumpeter’s discursively developed model emerges. First, the model adheres to the static (arguably minimalist) idealization of static equilibrium economics; the equilibria themselves are not subject to change, but the scale of the economy is. The only dynamism exists between equilibria when an entrepreneur innovates and changes the behavior or other market agents (see figure 1, below). This stands in contrast to the dynamic equilibrium of the Austrian discoverists, where dynamism exists within equilibria.

Figure 1. Static equilibrium, circular flow, move to higher “levels” due to opportunity creation.

Schumpeter describes this motion as “wavelike,” where the wave takes the economy to progressively higher “levels” with each innovation (despite some stakeholders being hurt from the change) (Schumpeter 1934, 69-80). It is also wavelike in the sense that periods of equilibrium are punctuated by waves of innovation (77). As a result of these innovations, the economy scales, and equilibrium is temporarily disturbed before reestablishing at another scale. So, as entrepreneurial innovation increases, entrepreneurial profits increase, because entrepreneurs take advantage of the fulfilment gap as the market re-equilibrates at scale (see red “opportunity” box in fig. 2, below). The circular flow is elevated to new levels by waves of opportunities, and the resulting “creative destruction” of capital forges a more productive economy (62-85). Economic development is thus a series of “separate partial developments,” rather than a dynamic whole, germane to Neoclassical theory (Schumpeter 1934, 77).

Figure 2. Rising periodic “waves” of innovation (represented as aggregate entrepreneurial profits, drawn as a rising periodic function [red]) raise the “level” of static equilibria by expanding the capacity of the economy via efficiency gains (represented as a rescaling of the quantity/price axes). The excess quantity and price created present opportunities for the innovative entrepreneur and the imitator since equilibrium statically rescales with the economy.

Evidently, Schumpeter’s entire line of reasoning is idealized to fit with mainstream Neoclassical theory. Below, I explore: how Schumpeter idealizes his own model to accommodate for the minimalist idealization in static equilibrium models, what this means for his inclusion and fidelity criteria, and how this model aspires for P-generality.

2.1.1 Schumpeter Idealizes his Development Model to Fit with Neoclassical Theory

It is evident that Schumpeter idealizes his model to fit within the broader framework of Neoclassical theory. The state reflected in Schumpeter’s development model is not as an alternative to static equilibrium, but rather an intermediary, periodic state between static equilibria caused by entrepreneurial innovation. To clarify that his form of dynamism poses no threat to the Neoclassical orthodoxy, Schumpeter’s goes as far as to explicitly assert that “there is no such thing as a dynamic equilibrium. Development…constitutes a disturbance of the existing static equilibrium and shows no tendency…to strive gain…for…any other state of equilibrium” (Schumpeter 1934, 76).

Nevertheless, Schumpeter’s must model economic development, which is a dynamic phenomenon. So, Schumpeter idealizes dynamism to be static. Schumpeter idealizes market opportunities as “inorganically” (read: statically) introduced by entrepreneurs, rather than “organically” (read: dynamically) produced by the market (76). He idealizes motion more as a transposition: as “separate” and “partial,” not as “whole” (which would risky “immanent” dynamism) (77). In essence—conceptually speaking—rather than move the picture, Schumpeter moves the frame (see fig. 2, above, for an applied transposition means).

Schumpeter’s idealization of motion as transposition, while heavily idealized, works because it includes only what makes a difference to shifting equilibrium while excluding any pathways that imply dynamic possibilities. I defer to Schumpeter’s own words to evidence my claim that Schumpeter idealizes dynamism as static transposition:

“…transposition yields an independent explanation. Economic development could be explained…just as the course of the static economy can be explained…One could consider it as a given fact that the satisfaction of needs is the same as a widening of the individual’s economic horizon.” (Schumpeter 1984, 72-3).

Schumpeter’s idealization could thus be justly described as minimalist—in line with the idealization evident in other Neoclassical models. Minimalist idealization is the thought process behind making (and interpreting) a model that only includes the most important requirements without which you couldn’t represent something as its intended self (Weisberg qtd. in Murataj 2021, 1). A requirement of equilibrium motion—of opportunities causing price and quantity shifts in an otherwise stative, equilibrated, perfectly competitive economy—is that the numbers of the quantity and price change. To achieve this within the Neoclassical framework, Schumpeter idealizes motion by simply changing the scales of the “axes” (see fig. 2, above)! This idealization is minimalist idealization at its most creative, and it has an interesting effect on Schumpeter’s striving for P-generality; in effect, this idealization spurs the opportunity debate.

2.1.2 Schumpeter Meets P-Generality’s Inclusion and Fidelity Criteria in a Unique Way

Representational ideals are goals that guide theorists’ modeling by describing which characteristics of reality to include in the model (termed “inclusion criteria”); and how “tightly” each part of the model should “fit” with reality (termed “fidelity criteria”) (Weisberg qtd. In Murataj 2021, 2). Schumpeter’s model can be construed to strive for any number of representational ideals, the most obvious being 1-Causal. However, Schumpeter explicitly disavows that his model strives to include all the primary causal factors accounting for opportunities arising from innovation-disrupted equilibrium, because he recognizes the indeterminate, individualized nature of innovation:

“In all frankness, we can say nothing about the driving forces of…development, we cannot touch the deepest causes of it. What is clear…is that we may not…isolate…development to…its elements. …we have to be satisfied with an indeterminate concept. But we can at least say in where determinism is present and where indeterminism is to be found, and then, in which kind and in which way this or that process of development will occur. What is certain is that we cannot use simple chains of causation.” (Schumpeter 1934, 113).

Rather than Strive for 1-Causal, Schumpeter strives for P-Generality. P-Generality guides to create models that represent not only real targets, but also possibly real targets, such that the model includes both the actual and nonactual on a comparable “spectrum” (Weisberg qtd. in Murataj 2021(2), 2). Schumpeter’s adoption of P-Generality is directly evidenced in his discourse. In speaking of the interaction of social and economic causes that affect innovation, Schumpeter notes that his model of opportunity development is meant to reduce “causal chains” to “functional relationships” of “general interdependency, such that it is P-general enough to represent development even backwards, and even outside a market context:

“The essence of that [developmental] process lies in this [sic.] that one can consider the states of each field as the result of data [i.e., information], each of which are assumed to be immutable [i.e., static]. These data also include the states of all other areas of social life. The causal chain set up in this way…proves to be fertile…but its general explanatory value is…the fact that one simply can apply it to all of those fields, in particular that one can also reverse it. If one has e.g. explained the economy of an epoch from the data, which govern the social structure of a society, then one can also explain the latter in an analogous way from other data, including those relating to the level of the economy—which in that case itself is assumed to be invariant. …One will understand what is meant when we say that this fact will reduce the causal chain mentioned above to a functional relationship…of the “general interdependence.”” (Schumpeter 1934, 108).

Thus, Schumpeter’s fidelity criteria are quite broad; the model doesn’t necessarily have to apply to any specific case of economic development and entrepreneurs, but only to the general idea of development (see Schumpeter 1934, 100-114). Although Schumpeter does not give specific examples of his model applying outside of markets, it is easy to imagine one: consider Republican congressmen’s political economies pre and post Donald Trump (who is the equivalent of the “entrepreneur”). In this hypothetical, development even happens backwards. Thus, Schumpeter’s model embodies P-generality by representing a broad possibility class due to its relaxed fidelity criteria; this has the effect of giving Schumpeter “model jurisdiction” over a broad swath of dynamic opportunity representations, despite his theoretical limitations.

However, Schumpeter’s inclusion criteria remain narrow due to his Neoclassical allegiance, which leads him to resolve that “the transition from one state to the other can only follow according to static rules” (109). Schumpeter entertains the idea that “those states could also have been arrived at in a nonstatic way,” but follows up with “Nevertheless, this assumption is no longer possible when we want to take an overview of the states of all areas in a static way” (109). These narrow inclusion criteria keep Schumpeter’s model germane to neoclassical theory. E.g., they allow Schumpeter to ignore the possibility of asymmetric information and dynamic equilibria, which her terms “mere phenomena of adaptation” and considers them “as constants” (76). Further, Schumpeter defines the entrepreneur as a rare “leading man” of exceptional creativity and genius, restricting the scope of market participants considerably (82-90). This mismatch between the breadth of Schumpeter’s inclusion and fidelity criteria has the effect of allowing only for a narrow set of acceptable model-based explanations for a far broader class of phenomena.

Thus, Schumpeter’s model applies to a broad “jurisdiction” of opportunity-related phenomena but offers a limited set of explanations. I am tempted to term Schumpeter’s model a “selfish” embodiment of P-generality. These quirks in Schumpeter’s striving towards a representational ideal put him on a collision course with the Austrian discoverist camp—which strives for P-Generality with broader inclusion criteria and tighter fidelity criteria.

2.2 Kirzner’s Dynamic Discovery Model and Austrian Approach to P-generality

Contrary to Schumpeter, Kirzner—representative of the discoverists—holds that opportunities are exogenous artefacts of the market, arising from asymmetric information and exploited by entrepreneurs as part of the competitive price discovery process. This Kirznerian market differs significantly from the Neoclassical market, because market participants cannot learn from their participation (Kirzner 1973, 15). Buyers, trapped in the throes of asymmetric information, “do not discover that they could have obtained the same goods at lower prices;” sellers “do not discover that they could have obtained higher prices” (14).

Rather than fall into imperfect equilibrium, the Austrian market is dynamic—profit opportunities “exist because…the initial ignorance of the original market participants” leaves resources underpriced and solutions inefficient (14). Opportunities thus arise not from Schumpeterian moments of disequilibrium, but from the immanent, “organic,” suboptimal transfer of resources under asymmetric information about alternative uses. Here emerges the Kirznerian entrepreneur, who is neither a would-be seller nor a would-be buyer, but someone who perceives and acts upon opportunities for entrepreneurial arbitrage (14).

So, Kirzner understands opportunity as a matter of information. The main difference between Kirzner’s entrepreneurs and other market participants is that entrepreneurs learn from experience whereas the others do not (15). Unintentionally, the Kirznerian entrepreneur acts like a market “radio,” providing ordinary market participants with information about prices and demand in selling/buying to them. As a result, these entrepreneurs transmit price signals to ordinary market members, allowing prices to move as if buyers and sellers had symmetric information. The dynamic equilibrium that emerges in Austrian markets is reminiscent of Schumpeterian disruption, but by different means.

Rather than be exceptionally creative, Kirznerian entrepreneurs are privileged in their role due to “alertness,” an ex ante difference that makes it possible for these entrepreneurs to notice subtle changes in market circumstances that affect prices (15). In the Austrian model, Market circumstances change anytime a market participant acts upon the market (i.e., buys, sells, or offers an opportunity), because their actions have a ripple effect on prices which may create or void market opportunities (11-22). Kirznerian entrepreneurs exploit these opportunities by being “alert” to the effect of these rippling prices on the overall market, acting in anticipation, sometimes buying resources at a higher price than offered to compete with other entrepreneurs noticing the same opportunity (15). As these entrepreneurs exploit these opportunities, their competition “pushes prices in directions which gradually squeeze out opportunities for further profit-making” (Kirzner 1978, 15-6). In this “never attained state of equilibrium” (see fig. 3, below), entrepreneurial decisions to exploit opportunity dovetail (i.e., entrepreneurs buy and sell from each other) until rent-seeking drives rentability to zero, constituting a dynamic equilibrium.

Figure 3. Conceptual illustration of Kirzner’s entrepreneurs (represented by the red arrows) as the first to become alert to new opportunities resulting from situational changes. These entrepreneurs buy and sell form ordinary participants, giving them price signals and aligning the whole market around pricing opportunities until rentability is erased and a dynamic equilibrium is found.

Despite adhering to Austrian conventions, Kirzner’s theory of opportunity discovery is subject to considerably less constraints than Schumpeter’s. However, the methodological differences between the two camps are irreconcilable because Schumpeter fervently defends static equilibrium, which Kirzner explicitly disavows. Below, I delve into the little idealization that is present into Kirzner’s model, before exploring its representational ideals.

2.2.1 Austrian Idealizations in Kirzner’s Model

Austrian economics holds that market phenomena are solely the result of individual actions and incentives. As such, Austrian economics is partial to idealization only if it helps establish the Misesian concept of homo agens (qtd. in Kirzner 1978, 33). Kirzner keeps idealization to a minimum, as evidenced by his rejection of the “economizing man,” in line with Austrian teachings. Kirzner seems to employ idealization only in making the entrepreneur a market equilibrating mechanism, such that the entrepreneur serves as a proxy for human will in driving economic processes and opportunity discovery.

This idealization of the entrepreneur as a market mechanism permeates through Kirzner’s theory. Kirzner never relaxes his idealization, implying that it is not Galilean. Rather, Kirzner idealizes the “entrepreneurial element in human action” by capturing its most essential difference-making factor: “alertness” (Kirzner 1978, 33).

Kirzner elaborates that alertness is an “active, creative, and human” awareness of entrepreneurial opportunities for profit, rather than a characterization of market participants as “passive, automatic, and mechanical,” which satisfies Austrian human-centric assumptions (35). But, in practical terms, Kirzner’s alertness serves as a minimalistic differentiator between entrepreneurs (who are understood to be special) vs. other market participants. So, Kirzner idealizes the concept of alertness to enable entrepreneurs to act as distinctly gifted market equilibrators, so to make his model work.

Thus, Kirzner utilizes some measure of minimalist idealization in representing entrepreneurs to make his human-centered model work. Kirzner’s idealization differs significantly in method, purpose, and degree from that of Schumpeter, who idealizes several concepts (e.g., market information, competition, even entrepreneurs) to a far greater extent (in line with his looser fidelity criteria). This difference in the extent of idealization is at the source of Kirzner’s criticisms of Schumpeter, among their divergent approaches to P-Generality.

2.2.2 Inclusion and Fidelity Criteria in Kirzner’s P-General Model

Kirzner strives for P-generality only within the possibility class of economies, primarily evidenced by his classifying of his attempt as a “theory of the market” (1). He confirms as much by mimicking the language of Schumpeter early in his discourse, stating that his task is to “develop functional relationships” (rather than a causal analysis) between human-led market processes and “equilibrium” (1-7). Kirzner strives for P-Generality when he claims that all market phenomena—Schumpeter’s economic development explicitly included—result from entrepreneurial action (72). To Kirzner, economic development is a special case of his “entrepreneurial-competitive” process, where entrepreneurship is the “equilibrating response to preexisting tensions” that resolves inefficiencies with development (Kirzner 1973, 130-131).

Thus, Kirzner’s model embodies P-Generality because it applies to theoretical cases (such as Schumpeter’s development) outside of its immediate purview. However, unlike Schumpeter’s, Kirzner’s economic model is restricted in the possibility class that it can represent (market economies). Whereas Schumpeter’s model can represent development in fields other than economics (e.g., sociology), Kirzner’s is limited to phenomena of market economics by its stringent fidelity criteria (which demand a far higher degree of a-generality than Schumpeter’s)—Kirzner requires that any and all model components strongly mirror reality.

Kirzner’s model’s inclusion criteria, on the other hand, are broader than Schumpeter’s model’s. Rather than abstract away entrepreneurial qualities and take the entrepreneur for granted, Kirzner provides alertness and asymmetric information. Rather accept static equilibrium, Kirzner accommodates for a dynamic equilibrium due to competitive rent-seeking. Without formalist limitations on his theory, Kirzner is freer to consider various properties of market phenomena. So, Kirzner presents a model that is (philosophically) a mirror opposite of Schumpeter’s approach: a P-General model with stringent fidelity criteria and looser inclusion criteria, employing minimalist idealizations less that Schumpeter’s.

This difference in modeling—satisficing the equilibrium framework vs. proceeding unhindered—is termed “methodologically unacceptable” by Kirzner (66). I take Kirzner’s stance to evidence my claim that the root of the opportunity debate is due to mismatched fidelity and inclusion criteria. Below, I take the models previously extracted from the discourse and I identify the source of their disagreement.

3. OVERLAPPING POSSIBILITY CLASSES AND INCOMPATIBLE CRITERIA

Based on the previous discussion, I claim that Schumpeter creates a heavily idealized model of created opportunity and strives for P-generality with strict inclusion criteria and broad fidelity criteria. I also claim that Kirzner creates a “lightly” idealized model of discovered opportunity and strives for P-generality with broad inclusion criteria and strict fidelity criteria. Schumpeter’s restrictive inclusion criteria in tandem with his broad fidelity criteria mean that Schumpeter’s model simulates a restricted set of “correct” representations for a broad variety of possibilities. On the other hand, Kirzner’s restrictive fidelity criteria demand that the fit of a model’s parts back to economic reality must be “tight,” but his model’s broad inclusion criteria demand that nearly any aspect of an economic system can be modeled within the entrepreneur-as-an-equilibrator framework.

I argue that these two models of market opportunities, in striving for the same representational ideal via different criteria, offer incompatible explanations for the same market phenomena. Since I previously discussed the textual and theoretical evidence underlying this incompatibility, I proceed by illustrating how these explanations differ by using each model to analyze an “edge-case:” Thomas Edison’s invention of the lightbulb and his mass purchase of bamboo. This example will hopefully help clarify the point at contention by these two approaches.

3.1 Application of Constructivist and Discoverist Models to Thomas Edison’s Arbitrage

Thomas Edison received a patent for the light bulb in January of 1880. Prior to his patent, Edison had been experimenting with different materials to create a lasting filament for the lightbulb. After much experimentation, Edison discovered that carbonized bamboo filaments—from Japanese bamboo—burned the brightest, longest, and cheapest. Being an entrepreneur and an inventor, Edison saw a market opportunity. Edison proceeded to enter into exclusive contracts with nearly all major Japanese bamboo producers, ensuring that, when his lightbulb entered the market, he would control the world’s bamboo supply in addition to the intellectual property protections for his lightbulb.

The Edison case is interesting because Edison is, in this case, both a “creator” and a “discoverer.” As a result of his activity, the market equilibrium for bamboo should have noticeably shifted.

The Schumpeterian model would characterize Edison’s opportunity for rent a result of his innovation. By innovating the light bulb—knowledge yet unknown by the market—the static equilibrium for bamboo would “expand” and Edison could take advantage of the price-quantity differential to earn temporary rents. So, in the Schumpeterian view, Edison created an opportunity and took advantage of it.

The Kirznerian model would characterize Edison’s arbitrage as a market opportunity emerging from information asymmetry. According to Kirzner, it is not important that Edison invented the light bulb—rather, it is only important that, through his asymmetric knowledge (i.e., his invention), Edison had become “alert” to a more valuable alternative use-case for bamboo. Others did not take advantage of the bamboo trade because they did not have the same information as Edison. Thus, the discoverist camp would hold that Edison’ opportunity did not come from his innovation per se, but rather from the fact that he had asymmetric information about the alternative uses of bamboo filament, his innovation happening to be a major one.

3.2 Identifying the Point of Contention between Constructivist and Discoverist Models

From this conceptual angle, the point of contention between the constructivist and discoverist approaches appears to be their different comprehensions of market dynamism. The constructivist view favors punctuated dynamism whereas the discoverist view favors continuous dynamism. This contention arises not as an intrinsic property of the approaches, but rather as an artefact of their application (and applicability to) to the same subject (e.g., the Edison case).

Since both approaches strive for the same representational ideal (P-generality) with different inclusion and fidelity criteria, applying both to a situation where either can apply results in different conclusions about which aspects of the target are relevant to the model and how closely the model must correspond to reality. The discoverist model strives to be more realist than the constructivist model (as evidenced by its stricter fidelity criteria) and it cannot reconcile its fidelity judgements with the low-fidelity explanations of the constructivist model. The constructivist model is also more idealized than the discoverist model (due to its Neoclassical constraints), and its tight inclusion criteria breed ontological contention with the discoverists due to the constructivist model’s inability to accept the irregular, dynamic inclusion criteria of discoverist models. I term this conceptual phenomenon “cross-incompatibility.”

This cross-incompatibility stems from these models’ grounding in Neoclassical vs. Austrian economics, which developed to be incompatible; thus, as an heir of the Neoclassical vs. Austrian equilibrium, information, and entrepreneurship debate, the opportunity debate is relegated to the same foundational issues.

CONCLUSION

I leave the debate about whether opportunity is created or discovered unanswered for the purposes of this paper. Fundamentally, this debate originates from “cross-incompatibility” of criteria in models striving for the same representational ideal. Perhaps it can be generalized that this “cross-incompatibility” exists at a broader level between Neoclassical and Austrian economics. Whatever the case, the debate about the ontology of opportunity has its roots in differing methodical approaches, and—if models are considered epistemological devices—this debate hints at an epistemological incompatibility between these camps.

Hopefully, as scholars (like Schlaile et al.) approach this debate with new conceptual tools (e.g., memeplexes), the field of entrepreneurship might be able to derive fundamental truths about opportunity without resorting to the concepts of Neoclassical and Austrian economics. These frameworks are too mired in incompatibility for constructive dialectic. For mathematical or computational models, where the target is represented in some static schema, a mathematical system for resolving cross-incompatibility could be introduced (see Yingxu Wang’s work on concept algebra and abstract algebra methods for inspiration)—I leave this further work to be conducted my a more qualified (and hopefully better compensated) scholar.